A couple of days ago John wrote about the seemingly new doctrine of armed response to acts of cyber sabotage. I’m broadly with him on the badness of expanding without limit the range of events that we would treat as an act of war. But I think there is much less new here than it seems — and perhaps that lack of novel insight is more of the problem than the risks inherent in treating cyber attacks as a potential casus belli.

First of all, there is a significant trail behind this latest Pentagon statement. A major milestone came with the publication of Presidential Decision Directive 63 in 1998 — a document coming from the Clinton White House/National Security Council. The directive calls for a series of measures aimed at minimizing our vulnerability and enhancing our ability to respond to cyber attacks — response in this case meaning fixing the damage to critical systems to minimize pain, suffering, and economic and/or military damage. But the notion that a digital attack is a form of warfare is already present, part of US official doctrine all the way back in the last century:

Because of our military strength, future enemies, whether nations, groups or individuals, may seek to harm us in non- traditional ways including attacks within the United States. Because our economy is increasingly reliant upon interdependent and cyber-supported infrastructures, non-traditional attacks on our infrastructure and information systems may be capable of significantly harming both our military power and our economy.

And of course, this is true. As the WSJ article to which John linked recounts, the Stuxnet virus that seems to have done significant damage to Iran’s nuclear effort struck at a sovereign nation’s economic and perhaps military capacity in a pretty direct way.

Had the authors of Stuxnet managed to set off a bomb in the centrifuge room, that would have been obviously an act of violence, one of war. That the cyber path permitted the same damage to be done less messily does not alter its tactical significance, at least not in any obvious way. If the Pentagon is moving to formalize the logic implied by Clinton-era perceptions of cyber threat — well, there are changes here, but I’m not sure they are as groundbreaking as the WSJ article made it seem.

That is: the reality behind the digital metaphor of infection is one of the facts of life in a networked world. The realms of the virtual and the physical are now deeply interconnected, and disruption of the cyber networks can (and has) produced real consequences in our material circumstances. I don’t see it as a huge stretch to suggest that a cyber attack could cause the deaths of people, and that a response using other weapons that also kill people might be appropriate, if (and only if) you can reliably connect the original attack to the folks you want to target.

Which is the real problem with this not-so-new posture, a twisty little bit you can find by burrowing a little deeper into the WSJ piece:

Pentagon officials believe the most-sophisticated computer attacks require the resources of a government. For instance, the weapons used in a major technological assault, such as taking down a power grid, would likely have been developed with state support, Pentagon officials say.

Well, maybe. But I read this and come back to where I think John was heading in his piece: if a network attack by a cyber-al-Qaeda goads us into pounding the next Iraq stand-in, then we are back to what got us into our current predicament in the first place.

To which depressing thought, I’ve three reactions.

First: it is a good thing that our government is taking cyber crime/war seriously. Given how increasingly dependent we are on a complicated and variously vulnerable digital infrastructure, it would be the height of folly to think that our networks are of no interest to potential adversaries.

Second: its an assumption not in any evidence I’ve seen these adversaries will be conventional states, to be deterred or defeated by conventional means.

The idea that cyber skills are uniquely the province of nations, or that digital assaults require the same kinds of concentration of resources needed to field actual armies is as unsupported as the notion that no band of committed nothing-to-losers couldn’t strike at major civilian targets in the United States.

So if in fact the focus of this new cyber command is mostly committed to state actors, I don’t feel much more secure for its existence. Worse — if our only options in response to cyber attacks are ordinary military strikes on conventional physical targets we’ll be right back in the sad old game of shooting at the wrong people with the wrong weapons…which is no damn good at all.

Third: It’s not in the piece, and though I’ve been following some of the writing about cyber security popping up lately, I’m hardly expert. But I do worry about what I see as at least a potential trap in the way we might be imagining cyber threats. A lot of conventional, garden variety digital security is based around the idea of building a fence around a vulnerable system — that’s the idea of a firewall that keeps malware and intruders out of yours and my personal computer, or the systems to which we attach in the course of our working day.

I’m hoping that’s not how the new cyber-command — or rather, its superiors in the chain of command — are thinking. If the concept of cyber-security being developed by the national security folks is based some kind of digital Maginot Line, an über firewall designed to keep the bad guys out, then we may well be fighting the last war. Because, as we’ve seen with major security breaches in commercial networks, the real vulnerability happens when someone gets past a security wall, whether by clever hacking from without, or old fashioned human treachery from within. If the folks directing our national cyber defence are Fulda Gap types, people with a strategic sense born of classic war-fighting approaches, then we’re in for trouble.

Early days, but my own web paranoia is peaking, and I have a deep urge to encrypt everything down to my cat Tikka’s 313131122’s name.

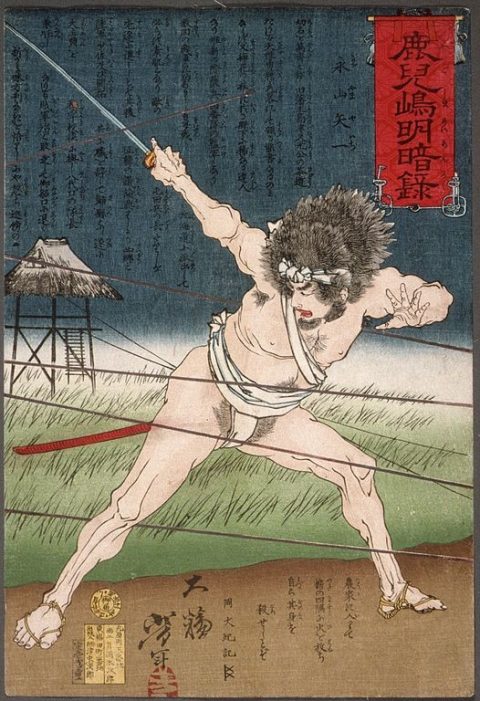

Images: Giovanni Batista Tiepolo, tentatively identified as the victory of Gaius Marius over Teutonic tribes in 101 B.C.E., c. 1725-1729

That’s another way of saying (a)

That’s another way of saying (a)

Recent Comments