I think it’s always a serious risk to disagree with Adam; he’s basically always right. But I do find myself differing from him on one question: is The New York Times actively trying to deny Hillary Clinton the presidency, or are their actions better explained by a less evil, more dangerous tendency?

Adam’s on the overt evil side: they’re trying to shiv her side. I’m thinking that what we’re seeing is an unconscious process, which is actually a much more difficult problem to tackle within elite political journalism.

My view: I communicate with some NYTimes people, and I’ve known some there for a long time, though I’m not in close touch with that cohort these days. I don’t have any contact with the Sulzberger/Baquet level, but below that I’m quite confident that there’s no conspiracy going on. If you could ask just about anybody at the Times, I’m sure they recognize that Trump is a shit show and all that.

But that doesn’t alter the problem there, the way the deck is nonetheless stacked at the Times and other top-echelon outlets.

A big part of the reason, ISTM, is that within a lot of journalism there is a very particular definition of what a story is, and the concept of accuracy is narrowly defined. A story need not be about facts, but about claims of alledged facts — Clinton’s emails raise pay-for-play concerns; and to be accurate such a story need only rise to the level of “some see in the new email release more indications of a pay-to-play connection to the Clinton Foundation.” That is — the fact that someone is willing to say such a dreadful deed took place makes the statement and the story “accurate” even if no reasonable reading of the underlying material suggest such nefariousness actually took place.

That paradigm leads The New York Times and the rest of them to make the same mistakes over and over again — and to get played in the same way seemingly every week. The right wing media activist camp — think Judicial Watch and the email farrago — is very good at pushing the story buttons, and you have a circumstance where the Times bites, over and over again, and finds itself once again dipping into the Clinton well.

What makes that so wretched is that if The New York Times were anti-Clinton in the way, say, Fox News is, there’d be an obvious counter: consider the source. But because this is done within a framework that the top practitioners believe is the right way to do journalism, pushback often serves to confirm their judgment in their own eyes. If partisans complain, they must be doing something right. And given that the elite media basically talks to itself, it’s hard to insert a corrective, though I and many others are trying to do so on and off social media.

It’s also important to note that the Times did engage the Trump-Attorneys General bribery story today, placing it prominently on the website. There are some oddities in the story — not uncommon for a publication playing catch-up. And the test will be the follow up: how deeply the Times chooses to pursue each of the elements of the story in the days ahead. If they do give it the full effort, then (a) that will be good and (b) it will suggest that much of the crap coverage of Clinton we’ve seen is the product of pre-existing bias (Clintons are yucky) combined with the story dynamics and incentives discussed here.

There’s an interview with Bob Woodward that the Harvard’s press office published today that to me expresses the problem of a Village, an epistemically closed community of practice that can’t easily interrogate the ways its own methods undermine the mission that they do in fact, sincerly, believe they’re pursuing. Woodward says:

Bob Costa, a reporter at the Post, and I interviewed Trump and we published the transcript and there are all kinds of things in there. For instance, he says, “I bring out rage in people,” and he’s proud of it. He forecast a giant recession, he was very pessimistic about the economy, and since then it’s only done better. He was asked, because he was running in the primaries in the Republican Party, a party that contained Lincoln and Nixon, “Why did Lincoln succeed?” And Trump’s answer was, “He did some things that needed to be done.” [We then asked,] “Why did Nixon fail?” “Because of his personality.” And we had to say, “Yeah, but his criminality was part of it.” And Trump said, “Oh, yeah.” It tells you who he is.

The same with Hillary Clinton. There were just voluminous stories on her. Let me give you an example from The New York Times, Feb. 20, 2016, a two-part series they did on Hillary’s role in Libya. It explains her role, exactly what she wanted to do. At one point, after [Libyan leader Moammar] Gadhafi’s death, it quotes her saying to some of her staff, “We came, we saw, he died.’ There was a series of spectacular Post stories about the Clinton Foundation, about her time at the State Department, and so forth.

The Trump interview is a story, sure. It was accurate, in the sense that I’m sure Trump said what Woodward and Costa said he said. It’s not revealing of very much — like what Trump has done and what his actions in the various enterprises he’s undertaken would tell us about a potential Trump presidency. But its accurate.

More important for the discussion of Clinton and whether press treatment of her reflects conscious or unconscious bias is the comparison between the kind of material Woodward celebrates as journalism about Trump vs. what he recognized in the Clinton Coverage. The Libya story he cites is a perfectly reasonable one one, exactly what you’d expect a newspaper to do. The Clinton Foundation stories…not so much, and so on.

The point’s obvious, I think. All of the stories listed above are “news” in some way. They meet (mostly) the narrowest criterion of accuracy. But they add up to a very different body of work, and evidence of very different approaches to the two candidates, born, I think, of the construct of the “sweet story” much more than of a planned journalistic campaign to derail Hillary.

TL:DR? You don’t need to invoke malice. An intellectual laziness* born of bad craft habits and professional norms fully explains what we see — which is bad news, as that’s harder to fix than explicit enmity.

*I don’t mean to suggest that Times journalists and their peers elsewhere are lazy in the sense that they don’t work hard. They work constantly for (in almost all cases in the print world) relatively short money. I’m just saying that they don’t sufficiently train the traditional journalist’s skepticism on their own endeavor, and so find it very hard to credit outside criticism, or to recognize what it is in fact they’re doing, not just day by day, but summed over the life of a campaign.

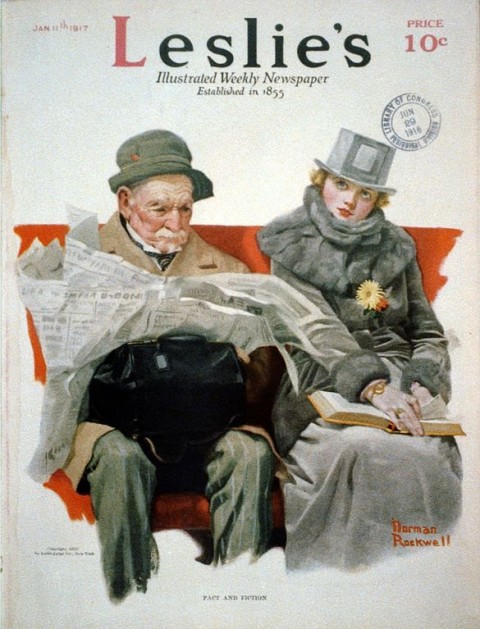

Image: Francisco de Goya, Fool’s Folly, 1815-1819

Recent Comments