Cross posted at So Simple A Beginning.

Up to now, we’ve been talking around the edges of what Darwin said to ease his readership into his ideas. Now it’s time to dig into the meat of the introduction to The Origin. (Past time, given the week or more that has passed since the epochal birthday – the celebration of which has already given at least one learned observer a bit of a hangover. What would Chris Norris think of a whole year, give or take, immersed in Mr. Darwin’s Abstract?)

So to begin: It’s going to take me a moment or two to get there, but what I want to point out here how much debt, and how much use Darwin makes of an approach to scientific argument originated by someone who is often seen as something of the anti-Darwin in subject, personality, and style. That would be the one man with a clear claim to the title of greatest English scientist ahead of the master of Down House: Isaac Newton.

It seems an unlikely comparison. Opinions divide on the quality of Darwin’s prose, but there is no doubt that The Origin is at least a reasonably painless read. Not so the Principia, even in its best translations. (Here is my choice for an English version, which comes complete with Newton’s text and an invaluable guide to the work by the great Newton scholar I. B. Cohen.)

Where Darwin coaxes, Newton commands. Only once as I read the text does Newton break character and seem to give in – just a little — to the urge to persuade. In Book III, as he describes how his new mathematical physics allows him to predict the paths of comets, he writes, “The theory that corresponds exactly to so nonuniform a motion through the greatest part of the heavens, and that observes the same laws as the theory of the planets and that agrees exactly with exact astronomical observations cannot fail to be true.” (Book III, prop. 41, problem 21.)

Even here, of course Newton buttresses his claim with a three – step chain of logical inference. The big stick of a formal proof seems to lurk in the shadows. Still, that “cannot fail …” has a hint of rhetorical pressure, there to give its push to the reader.

Against such a modest expression of a hope for the reader’s assent, Darwin is ever-ingratiating, almost deferential.

After explaining the sequence of events that led him to write The Origin, for example, he begs that “I hope I may be excused for entering on these personal details, as I give them to show that I have not been hasty in coming to a decision.”

On the significance of the observation of domesticated animals, he almost craves pardon, writing that “I may venture to express my conviction of the high value of such studies, although they have been very commonly neglected by naturalists.”

Even when he states the central theme of the Introduction and the work as a whole, Darwin remains unfailingly polite, and conscious of the sensibilities of his reader. In the paragraph on page 3 in which Darwin finally stops clearing his throat, he writes:

“In considering the Origin of Species, it is quite conceivable that a naturalist, reflecting on the mutual affinities of organic beings, on their embryological relations, their geographical distribution, geological succession, and other such facts, might come to the conclusion that each species had not been independently created, but had descended, like varieties, from other species.”

But for all the quites and the mights here, there is no disguising the muscle beneath the softness, as tough as Newton’s declaration that herein lies truth. What follows actually bears more connection to Newton’s approach to the presentation of radical argument than may be obvious under the warming blanket of Darwin’s verbiage.

Remember: Newton, for all the seeming artlessness of Principia – its apparent “just the facts ma’am” sequence of one demonstration after another –produced a book with a clearly articulated structure that enhanced the power of the content itself.* Crucially, in his introductory material, he laid down his famous three laws of motion as axioms, principles known (or to be seen) as true from which all else could be derived.

Newton’s use of this device was not new, (he said himself that he modeled his book on the works of the ancients) but it hadn’t been used in this way in the context of the new science of the seventeenth century, and he deployed it in the Principia to devastating effect. By developing a seemingly exhaustive analysis of matter in motion based on the derivation of theorems from that handful of basic principles, Newton laid claim to more just the truth he proclaimed near the end of Book III. His book, like Euclid’s before it, promised a method to discover new truths — in Newton’s case, by subjecting motion to number, and thus to the rigorous scrutiny of mathematical analysis.**

Did this triumph have an influence on Darwin? Not directly. Those susceptible to its charms had to possess more stomach for mathematics (or, like John Locke, be willing to take the proofs on faith) than Darwin ever did.

But (at last, having travelled the long road home!) the introduction to the Origin shows the debt Darwin owed to the Newtonian style. For all the cushioning of the blow, the essence of what Darwin said as he summarized the chapters to come turn on the axiomatic presentation Newton had deployed to such effect 150 years before. Instead of Newton’s three laws, Darwin offers just two principles – but they are sufficient, he promises, to the matter at hand.

That is: the concept of the descent of one species from another – the proposition to be demonstrated — he wrote, cannot be affirmed “until it could be shown how the innumerable species inhabiting this world have been modified, so as to acquire that perfection of structure and coadaptation which most justly excites our admiration.”

And now, writes Darwin, it can be told: this modification takes place through the operation of just two facts of nature: variation and selection. On variation, Darwin says that “we shall thus see that a large amount of hereditary modification is at least possible, and, what is equally or more important, we shall see how great is the power of man in accumulating by his Selection successive slight variations.”

As for natural, as opposed to human or artificial selection – that too will gain the status of a truth universally acknowledged, in Darwin’s promised treatment of “the Struggle for Existence: amongst all organic beings throughout the world, which inevitably follows from their high geometrical powers of increase”:

“As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.”***

There is no deference here. No hesitation designed to obscure a possible discomforting moment for the reader. At the point of the issue Darwin does not obscure the hard truth: living things vary. That variance has consequences, and if we must reproduce,**** then those consequences will include the differential selection of those better able to survive (and reproduce again).

All this could be, of course, just rather long-winded glimpse of the obvious: that in The Origin of Species Darwin made use of the two concepts we all know he did, variation and selection, to organize all the observations and interpretations of nature to come.

I’m actually trying to say something a bit different (kind of you – ed.). Darwin’s ideas emerged for him from his close introspection on the mass of facts he collected on the Beagle and afterwards. But his presentation of theory of evolution to the public proceeds the other way round: within a brief, seemingly (and deceptively) simple logical structure, the facts follow theory. As Newton had before him, Darwin presented his work in a way that framed individual facts – the track of a comet, the existence of nipples on male chests – into a weave of logic and prediction such that both theories cannot fail to be true.

Darwin was not Newton. He would never put the matter quite that baldly. But even if Charles was more polite than Isaac, he was no less aware of the real claim he was making.

And this speaks to an issue that runs through a modern reading of any 19th century text on biology. It is a commonplace to say that Darwin got lots wrong, and that there is a lot that is missing in The Origin. In later posts, I’ll wrangle with what it means to say that Darwin made errors. But leaving aside much of what I think is anachronistic in the “trip the genius” game (both as it applies to Darwin and to Newton, inter alia), the point is that Darwin, like Newton, was concerned in his book with the issue of creating a world view, a way of understanding all the specific phenomena each man sought to analyze.

Here, the axiom-and-application model is key. It is the structural device through which Darwin asserted that he had a theory of evolution, in the full, robust Newtonian sense of the term. Darwin was not merely arguing for that the current state of knowledge suggested the modification of species: he was demonstrating the explanatory power of a view that showed how modification could account for both what was known, and what was to be discovered. Q.E.D., for the last 150 years.

*I write more about the way Newton put together the Principia here, to be available in June.

**The phrase “to subject motion to number” originates with Alexander Koyré, who applied it to Galileo. It works here too.

***To be sure, by the end of the book the catalogue of biological laws expands to five: growth with reproduction; inheritance; variability; the struggle for life induced by high rates of increase; which induces natural selection, leading to divergence (of species) and extinction. The core ideas remain the same, however, or clearly logically connected to the starting two principles.

****In conversation about matters evolutionary with Olivia Judson this week, she pointed out that, of course, reproduction requires death; immortality would preclude sex (for those species that so indulge). I asked how many 18 year olds would choose deathlessness over sex; she answered, correctly in my view, none.

Images: A.Starilov, designer, USSR postage stamp, Scientists series, “Portrait of Isaac Newton (mathematician and physicist),” date of issue: 8th October 1987. (The image is a copy of this Sir Godfrey Kneller portrait of Newton completed in 1689.)

Newton’s first and second laws of motion, from the 1687 (first) edition of Principia.

Anton Braith, “Kühe auf dem Heimweg mit Hirtin” [Cows on the way home with their Shepherdess] 1860.

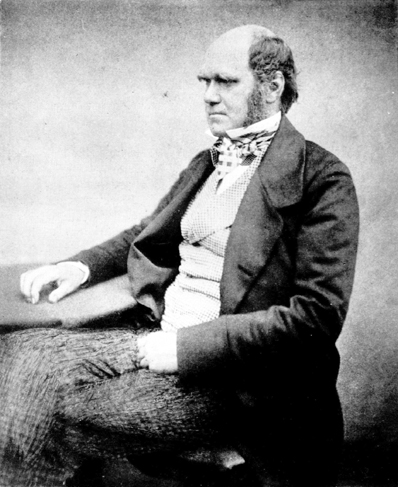

Image: Anonymous, “

Image: Anonymous, “

Recent Comments